Pragmatics of Human Communication is the title of a successful essay by Paul Watzlawick, Janet Beavin and Don Jackson (of the

Palo Alto School), which takes a systems approach to analyzing communication between humans. This text defines five axioms, or five aspects that are always present in communication between humans:

1st –

It is impossible not to communicate. In any kind of interaction between people, even with a gesture, facial expression or silence, something is always communicated to the interlocutor.

2° – Every communication has a

content and a

relationship (or

context) aspect, and the latter determines or influences the meaning of the former, constituting a

metacommunication (i.e., communication about communication). For example, if two people agree that they are joking, the meanings and consequences of what they say are different than if the people do not intend to joke.

3rd – Communication between two people is structured by

punctuation. This term means the identification of the beginning of interactive structures such as question and answer, action and reaction. It is an important aspect of communication because a reaction may give rise to a further reaction, and thus cause a

chain reaction in which there may be discordant views as to who initiated it, especially in cases of conflict or verbal violence.

4th – Communications can be of two types:

analog (i.e., images, signs, gestures) and

digital (i.e., words). That is, communication can be a mixture of verbal and nonverbal expressions, both of which are meaningful.

5th – Communications can be

symmetrical, in which the communicating parties place themselves on an equal level (e.g., two friends or two students), or

complementary, in which the interlocutors place themselves in different hierarchical positions (e.g., mother and child, teacher and student, etc.).

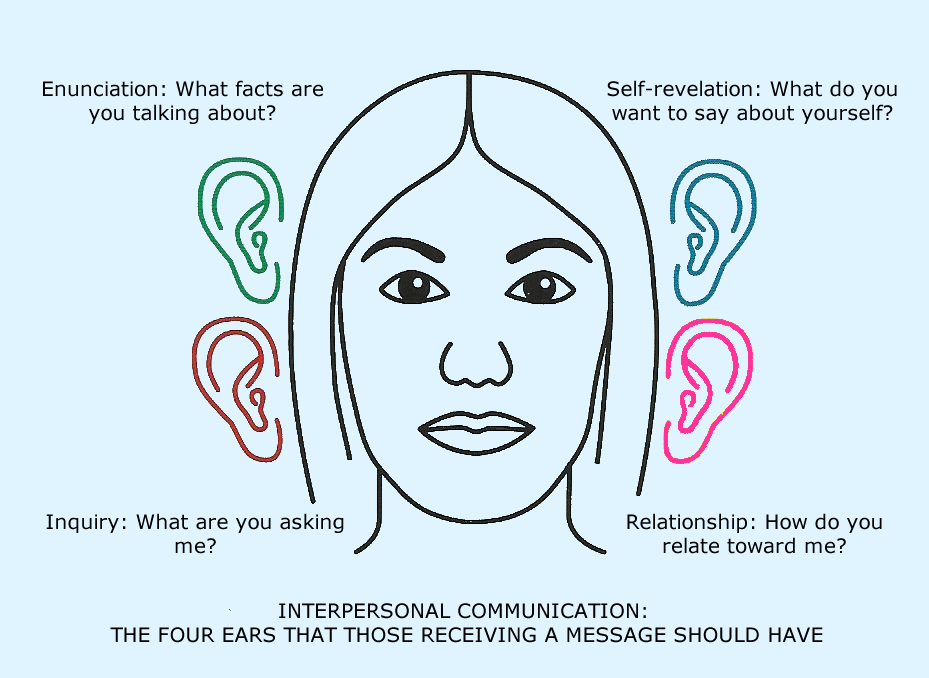

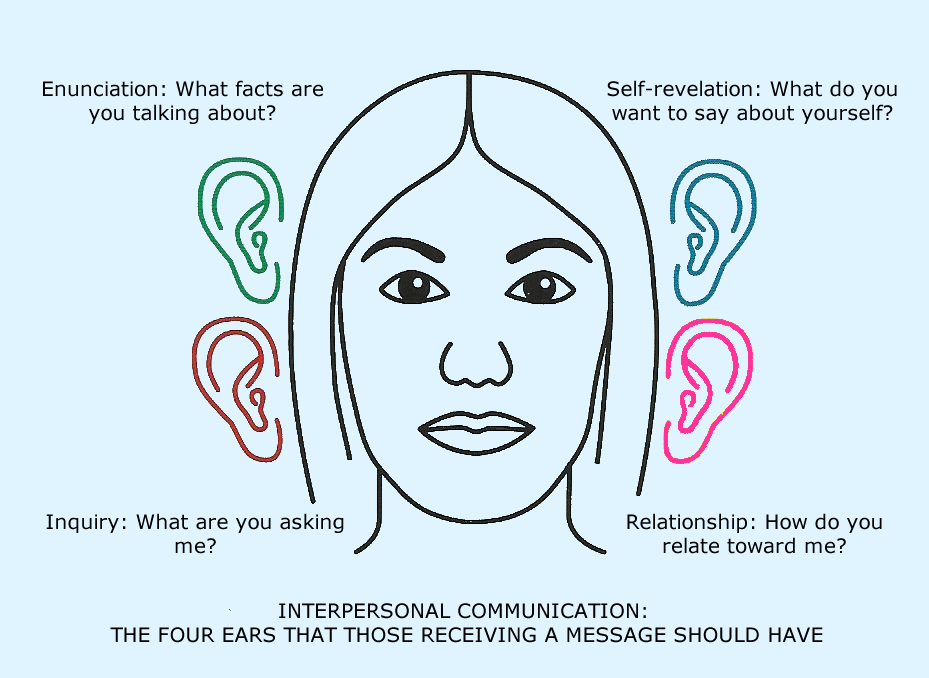

Following in the footsteps of Watzlawick and companions, Friedemann Schulz von Thun presents a model of human communication depicted in the figures below:

Schulz von Thun’s model, which does not replace that of Watzlawick & c. but is an extension of it, can be summarized by saying that each message contains four meanings:

- Enunciation: what are the facts the sender wants to communicate to the receiver?

- Self-revelation: what does the sender want to tell the receiver about himself?

- Request: what is the issuer asking of the receiver?

- Relationship: what relationship does the issuer assume to be in with the receiver?

Both models are useful for analyzing and solving communication problems between individuals and for improving the quality, that is, the effectiveness, of communication itself.

Communication vs. interaction

Communication is a subset of interaction, in the sense that in the interaction between two people there may be, in addition to communication (understood as the exchange of information), transactions of other kinds, such as the following.

- transfer of objects, goods, money, etc.

- transfer of energy (caresses, physical support, protection, sexual acts, etc.)

- provision of services (free or for a fee)

- exercise of violence (coercion, beating, wounding, killing, etc.).

That is why the title of this chapter is “Pragmatics of Human Interaction,” while evoking by similarity that of Watzlawick & c.’s “Pragmatics of Human Communication.”

However, it must be said that even a

noninformative transaction can constitute communication (i.e., an informational transaction) if the issuing and/or receiving parties associate a

communicable meaning with it.

Purpose of human interaction

What are the reasons why human beings interact? This question is more challenging than it may seem, because answering it requires appealing to general knowledge of human nature.

Consistent with the central idea of this book, the first answer to that question that comes to mind is that humans interact to (try to) satisfy their own and/or others’ needs, since without social interaction it would be virtually impossible to satisfy them.

In other words, human interdependence results in a need for interaction that goes hand in hand with the need for community that we have already discussed. Indeed, being part of a community implies the need to interact in certain ways with a number of its members.

Some might object that human beings interact not only to satisfy their needs but also for other reasons, for example, for pleasure, for enjoyment or to satisfy a religious injunction.

To such an objection I reply that pleasure and enjoyment, as well as obedience to religious injunctions, constitute needs in themselves, or means of satisfying higher-order needs.

I therefore remain of the view that everything man does (and particularly interacting with his fellow human beings) he does to satisfy his own and/or others’ needs, where satisfying others’ needs is a means of satisfying his own as well. In fact, man needs to satisfy the needs of others, for if he did not do so, he could not satisfy his own, for then he would not easily obtain cooperation from others.

Based on the above principle, let us see in what ways a person can satisfy his own needs and those of others through interaction. That is, let us try to define the basic aspects of a

pragmatics of human interaction.

Negotiation and cooperation

I assume that human interaction essentially serves to negotiate, prepare or exercise cooperation. I therefore divide interaction into two phases:

- negotiation phase (or preparation)

- cooperation phase

Negotiation basically consists of communicating to the interlocutor:

- what you are seeking, that is, what you need or want

- what you are willing to offer in exchange for cooperation aimed at satisfying your needs

- any conditions and rules (obligations, prohibitions, freedoms and limits) for cooperation

The duration of the negotiation phase may be longer or shorter, even very short (sometimes a glance is enough to complete it); it depends on the affinity between the interlocutors and the compatibility and correspondence of their demands, that is, the extent to which the demand of one

matches the supply of the other.

Negotiation may require several rounds in which each adjusts his demands and offers according to those expressed by his interlocutor.

In Schulz von Thun’s model, the elements of negotiation are well represented in the “request,” “self-revelation” and “relationship” aspects of the message. It must be said, however, that these aspects are normally almost hidden in the message, so understanding them requires a certain degree of empathy and

social competence.

In fact, it almost always happens that the negotiation phase is more or less cryptic, i.e., not explicit, not clear, neither direct nor frank, as if each party wants to be ready to withdraw its proposals and requests, even to deny them, in case it has the feeling that the other party is not willing to accept them. Indeed, there is often a fear of rejection, as if the rejection of one’s proposal corresponds to a lowering of status or social dignity.

Who is in charge here?

A crucial aspect of interaction, whether in negotiation or in cooperation, is the definition of the hierarchical relationship between the interactors, that is, the answer to the question “who is in charge here?” Both the question and the answer are politically incorrect in our culture, so they are normally removed into the unconscious or conscious hypocrisy. However, the question is always latent and emerges sharply whenever there is conflict or disagreement about what to do and not to do, and even about what to discuss and not to discuss.

Since it is usually assumed that in case of disagreement, one should do what the one who

knows best, that is, the one who is smarter and/or more educated on the subject under discussion, indicates, and since each would like to have the upper hand, each tries to prove that he or she is more knowledgeable than the other on the subject itself.

The same problem exists in the case of disagreement over adherence to agreed rules, where one partner accuses the other of not adhering to them, and the accused asserts the opposite.

Demonstrations (direct or indirect, implicit or explicit) of one’s own intellectual and moral superiority over the interlocutor are normally affected by self-deception (which we will discuss in the

chapter of the same name) whereby each person thinks he or she is the best person to determine what is best to do in case of disagreement.

In the end, one does as the less reasonable, less patient, less competent, or less intelligent person prefers, if the other cares about maintaining the cooperative relationship and preventing the partner from being disgruntled or frustrated.

What determines the success of a cooperative interaction

An interaction is successful when it sufficiently satisfies some needs of both interactors, meaning that for each of them the balance of the exchange is positive. That is, the weight of advantages (or gains) is greater than the weight of disadvantages (that is, costs or losses). I am talking about advantages in a broad sense, not limited to economic aspects.

For the balance of the interaction to be positive for both partners, the following conditions must be met:

- there must be sufficient correspondence and compatibility between what each asks for and what the interlocutor is willing to offer;

- each interlocutor must be able to express clearly and understandably his or her own requests and availability, and to understand those of the other;

- there must be a common understanding of the rules and conditions of cooperation;

- there must be a willingness and moral obligation on the part of both to abide by the agreed rules;

- there must be mutual recognition of each other’s intellectual and moral skills and abilities.

Satisfying the above conditions is all the more difficult the less explicit the negotiation of the interaction and the discussion in case of conflict. Consequently, it pays to resist conventions that advise against being explicit and direct in terms of expressing one’s demands and availability, as well as assessments of one’s own and others’ capabilities.

I hope this book will be helpful in knowing one’s needs in such a way that they can be expressed clearly to potential partners.

Next chapter: Mind games.

Schulz von Thun’s model, which does not replace that of Watzlawick & c. but is an extension of it, can be summarized by saying that each message contains four meanings:

Schulz von Thun’s model, which does not replace that of Watzlawick & c. but is an extension of it, can be summarized by saying that each message contains four meanings: