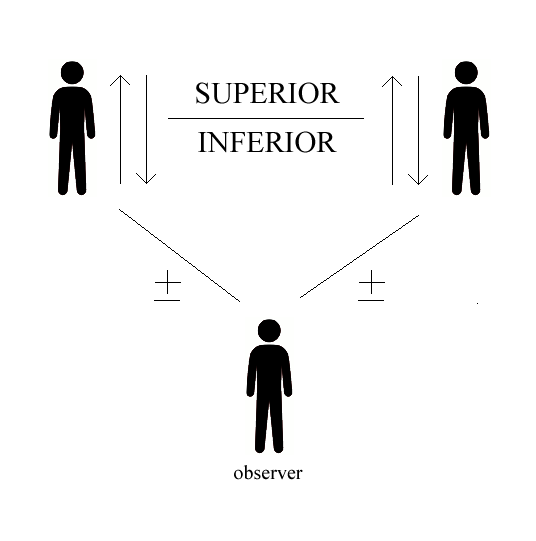

In my opinion, comedy, that is, the humorous effect, is related to the unconscious perception of the difference in social rank between two people, that is, the superiority or inferiority of one person over another in a general hierarchy.

In fact, I suppose that what snatches laughter is the immediate reversal of the superior/inferior relationship between two people due to a sudden change of context, which in turn brings about a change of meanings and values in the picture being observed or told.

I think this because I believe that every human being is constantly concerned (consciously or unconsciously) about maintaining or increasing his or her social rank, that is, above all, about not going down, and possibly up, in the overall hierarchical ladder of the community to which he or she belongs. This concern is due to the fundamental need of every human being, to belong to a community, and of the consequent fear of being marginalized or being placed in more disadvantageous positions than others.

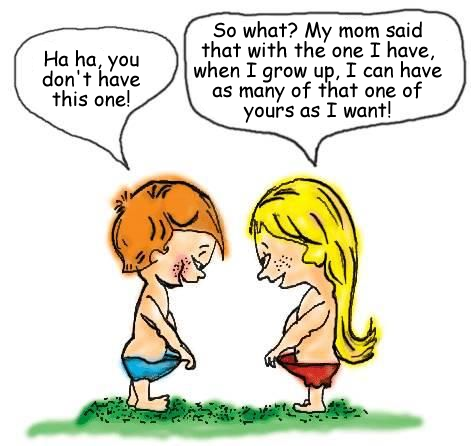

Take the following vignette as an example.

The comic effect of the vignette arises, in my opinion, from the sudden reversal of the superiority/inferiority relationship between the little boy and the little girl unconsciously perceived by the viewer, as a result of the following dynamic.

Initially we have a cognitive context in which the little boy is unconsciously perceived by the viewer as superior to the little girl. In fact the one boasts that he possesses something that the second one does not. But the latter’s response suddenly replaces, in the viewer’s attention, the initial context with a different one in which she is successful, that is, superior. In fact, the little girl convincingly demonstrates that what appeared to be a disadvantageous characteristic of hers is actually advantageous, much more so than that flaunted by her antagonist.

The comic effect is heightened by the fact that the little boy boasts of his superiority, so that his downfall is even more ruinous and the reversal of positions even more obvious.

It is interesting to note that the little boy’s sentence and the little girl’s sentence, taken separately, have no comic effect. Only by their juxtaposition does such an effect originate. This shows that what makes one laugh is not any element of the scene but a change in the context, and thus the meaning and value, of the elements of the scene itself, since only the context allows things to be given meaning and value.

Moreover, the comic effect requires that the change of context be unexpected and immediate. In fact, the longer the time elapses between key phrases in the two contexts, the weaker the comic effect.

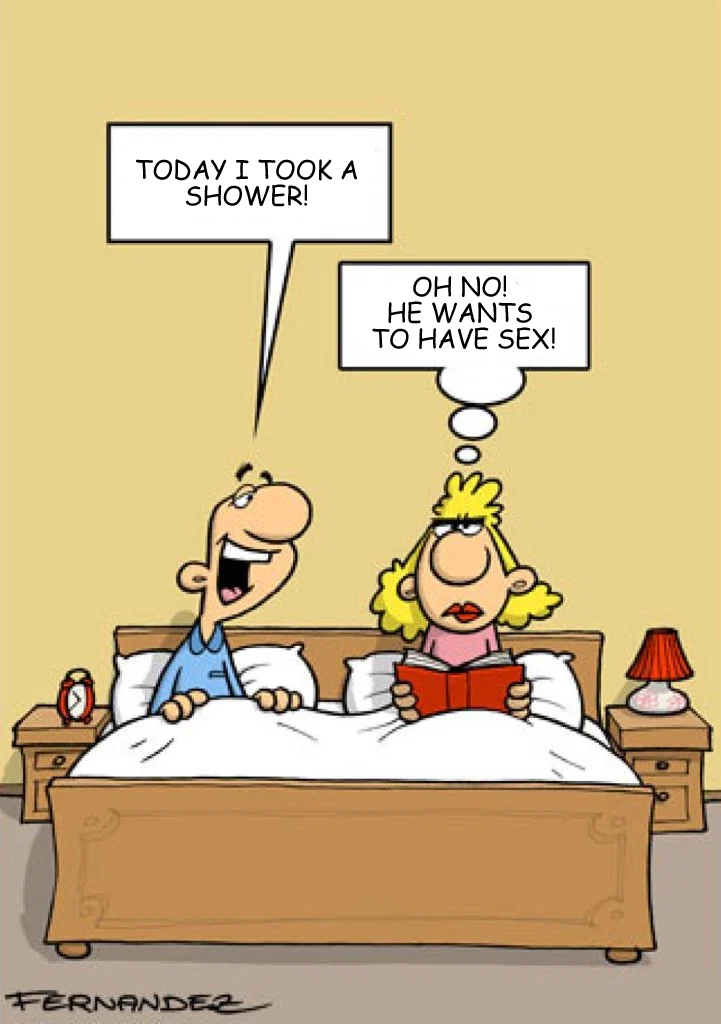

Let us take another example.

Here again we have an abrupt change of context and thus of meaning. In the first context (evoked by the first comic) we have a husband anticipating sexual intercourse that he believes he deserves having showered, evidently imposed by his wife as a condition. Thus we have a character who feels “high” and assumes that the interlocutor is at his disposal to fulfill his desire. The wife’s comic tells a completely different story, where the husband appears as a loser, either because his wife has no desire to have sex with him or because he proves to be a fool for not understanding the real situation. In short, in the viewer’s unconscious, in the first context the husband dominates, in the second the wife. The sudden change of dominator snatches a laugh from him.

One more example.

In a restaurant a man shouts to the waiter:

– Be careful! He stuck his finger in my soup!

– Don’t worry, it’s not very hot.

In this case, in the first context the customer is the dominus in that he scolds the waiter and the waiter is in trouble having done such a reprehensible thing as putting a finger in the soup. In the second context, on the other hand, the dominus is the waiter, who does not feel in trouble at all; on the contrary, he wins because he does not recognize the rule against touching the food to be served with his hands. His freedom from the rules is a winner, while the customer is a loser because his rights are ignored and he is disrespected. The little story is doubly comical in that it is not clear whether the waiter is teasing the customer, that is, challenging him, or does not realize that he has done something reprehensible, showing that he is quite clueless. This uncertainty is comical because it suggests a change in the waiter’s status from a brash figure to a stupid one.

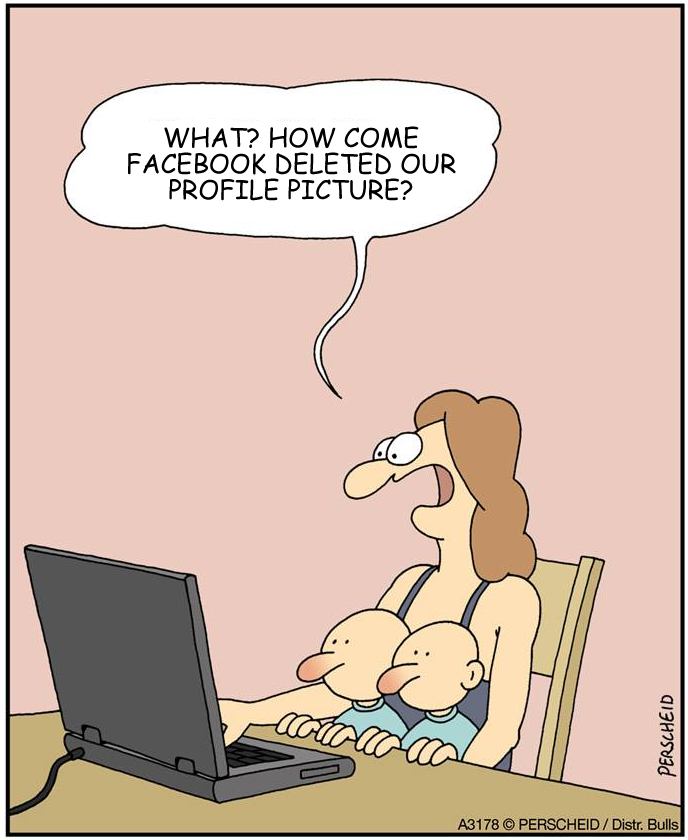

Let us finally examine this vignette.

Here the comedy is not related to the power relationship between two characters, but centers on the misadventure of a mother who does not understand what is happening to her. Here in the first context is a mom who does not understand why Facebook has deleted her profile picture. This is a serious thing that could happen to anyone, including the viewer, who therefore sympathizes with the character. In the second context, we find out the reason for the deletion, which reveals a certain stupidity of the character as well as the ugliness of her twins, mistaken by Facebook for mom’s breasts. In the sudden change of context, in the eyes of the viewer the character falls from a comparable rank with his own into a much lower one, so the viewer suddenly feels superior to the character himself and stops sympathizing with him. The comic effect is thus due to a change in the power relationship between the character and the viewer.

Comedy as sudden and final betrayal

We might at this point ask whether the change of context, that is, the change of dominator of the scene, does not involve a change in the viewer’s solidarity with the relevant characters. Indeed, in the case of the second vignette, we can assume that the viewer is initially sympathetic (i.e., sympathizing) with the husband, and that the change of context causes his solidarity (and sympathy) to shift toward the wife. This would be easily explained if we admit that there is in human beings a general tendency to side with the winners.

We might then think that the comic effect is due not only to the perception of a change in the balance of power between two characters toward whom the spectator is detached, but to the change in an unconscious affective position of the spectator who initially sides with a character, and then, following his sudden fall, betrays him to side with his antagonist who has beaten him.

If this hypothesis were true, it could be said that the comic effect implies betrayal on the part of the viewer, and laughter could be the psychosomatic effect of betrayal itself. In fact, the feeling of well-being that accompanies the laughter could be due to the perception of having made a good choice, of having overcome the anguished indecision about whom to side with affectively. After the twist, the power relations become decidedly, caricaturally clear, and the viewer can wholeheartedly and con-vincedly side with the winner, which results in relief as sudden as the laughter itself.

In the light of my reflections, I believe that humor is little studied from a philosophical and psychological point of view despite its enormous importance in social life. Just think of all the times we laugh or try to make people laugh when in company, and all the books, movies and comedy shows out there. The reason for this disinclination of philosophers and psychologists, as well as ordinary people, to investigate the deep roots of humor and comedy is, in my opinion, that these roots are politically incorrect. For in them come to light aspects of human nature that are ethically reprehensible, such as an interest in social rank, the pleasure of seeing others descend in the hierarchy (since any lowering of others automatically corresponds to one’s own elevation) and the tendency to sympathize with the victors.

Comedy as a sudden servant/servant role change

Another possible key to understanding humor might involve, instead of status change (superior/inferior), role change (cooperator/servant).

Take for example the following vignette.

In this case, in the first context there is the offer of a service consisting of the possibility of petting an animal in a kind of small petting zoo for children. In the second context we suddenly realize that the real intention of the offeror is to obtain from the unsuspecting customer a sexual service. In other words, the one who initially had a role as a bidder suddenly becomes the user of a different service, and a censorious one at that.

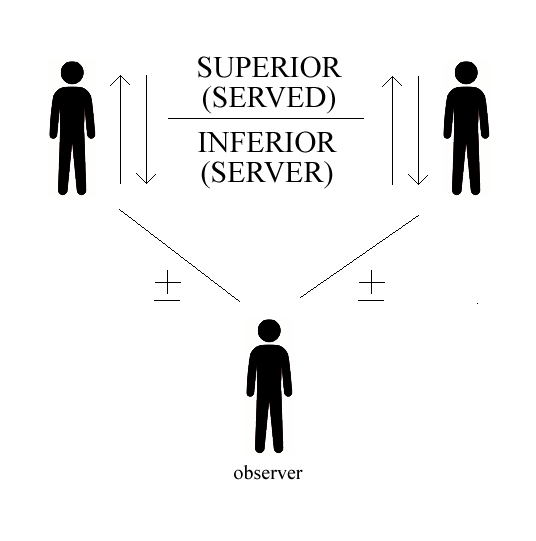

This schema (servant/served) is actually a variant of the schema (superior/inferior) in that we consciously or unconsciously associate superiority with the privilege of being served, followed, and obeyed by inferiors, and inferiority with having to serve, follow, or obey (a)superiors.

The combination of the two patterns (superior/inferior and servant/served) has the strongest comic effect. I am referring to the case where in the first context A presents himself to B as his servant, ready to help and obey him, while in the second context he is revealed as his dominator and exploiter. The second character is suddenly mocked, and the unexpected mockery wrings laughter out of the spectator, who was in the first context sympathetic to B as a servant, and in the second context sympathetic to A as a mocker.

Next chapter: Summary of the Psychology of Needs.