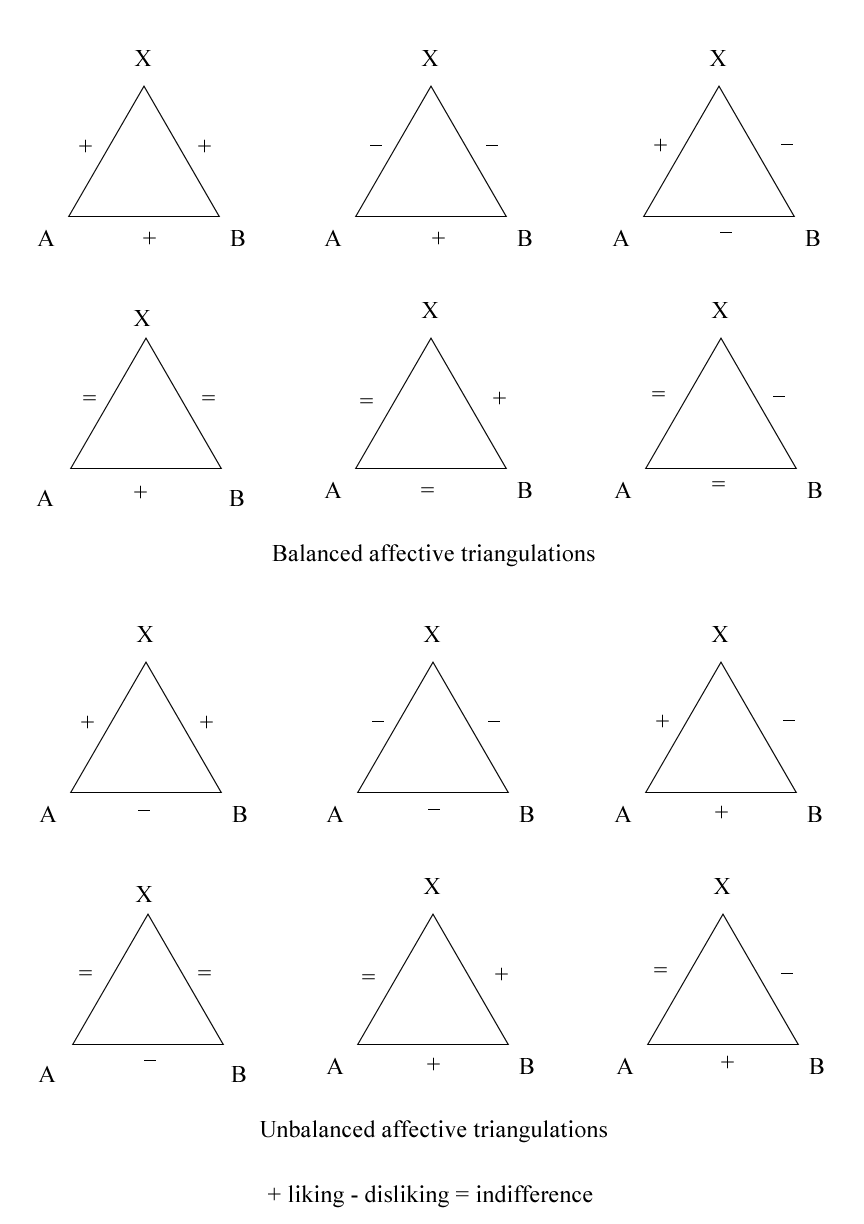

Affective bilateral relationships between two individuals are in fact almost always trilateral or, multi-trilateral in the sense that they involve a number of third entities (people, things, media, actions, ideas, etc.) with which both individuals have an affective relationship. According to Fritz Heider’s Equilibrium Theory (commonly and improperly translated as Cognitive Equilibrium Theory — in German Balancetheorie), in the relationship between two individuals, the sharing of feelings (liking or disliking, attraction or repulsion, etc.) toward the same third entity contributes to the determination of a positive affective bond between them. In such a case, the trilateral relationship is called balanced. Conversely, an affective discordance toward the same third entity (e.g., appreciation of a third person by the former and disdain for the same by the latter) contributes to determining dislike or hostility between the two individuals. In such a case, the relationship is called balanced. According to Heider’s theory, an unbalanced trilateral relationship results in a state of mental stress in the people involved and the consequent activation of dynamics (conscious or unconscious) that tend to rebalance the relationship. The following figures illustrate the above theory.

Take, for example, the case of the affective relationship between two individuals A and B, and their attitudes toward a third entity X where:

- A and B appreciate each other

- A appreciates X

- B despises X

In this case, the affective triangle is unbalanced because of the different affective attitude toward X. Three alternatives are possible to rebalance it:

- A stops liking X and starts despising him

- B stops despising X and starts appreciating him

- A and B stop appreciating each other and start despising each other

The three solutions are depicted in the figure below.

The conscious or unconscious logic underlying this theory could be summarized in the following sentences:

I like people who like things or people I like, and who dislike things or people I dislike.

I don’t like people who like things or people I don’t like, and who don’t like things or people I do.

The above does not apply in the case of competition between A and B to gain X’s favor. In that case there will be a minus sign between A and B, and a plus sign between A and X and between B and X, and the triangle is unlikely to find equilibrium. Heider’s theory has important implications that, in my opinion, have not been given enough consideration by the various schools of psychology and psychotherapy. It, in fact, reveals to us the general trilaterality of human interactions, in the sense that the relationships between two individuals are almost always mediated by third entities known to and affectively connoted by both parties, such as the following:

- language (syntax and semantics) used to communicate

- knowledge (learned scientific and literary background)

- moral principles

- aesthetic principles

- mode

- consuetudes and rules of interaction

- political goals

- economic goals

- authorities

- etc.

With respect to such third entities, two individuals may have more or less convergent or divergent feelings, cognitions and interests. In other words, about each entity there may be some degree of agreement or disagreement.

Immediate vs. mediated interactions

In my opinion, immediated relationships between two people, i.e., not mediated by third entities such as those listed above, are very rare and often violent, as they are neither limited nor protected by mutually accepted rules. Even in cases where two people freely negotiate the rules of their interaction and collaboration without reference to third-party entities, the negotiated rules become the third-party entities that the people agree to abide by. In fact, the third ruling entities in a relationship between two people can be given a priori (as cultural factors) or can be negotiated by the people involved.

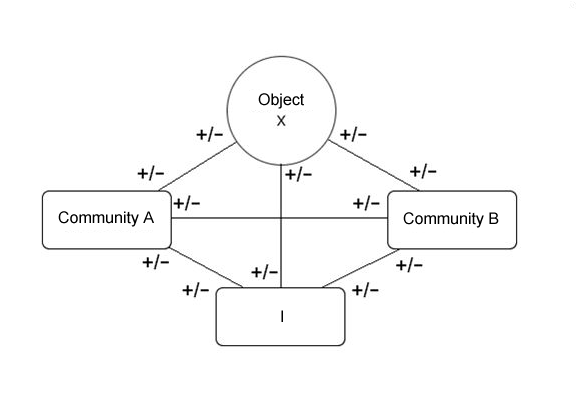

Role of communities in human interactions

The membership of a person A in a community X implies a number of triangles where A and X are two corners, and the third is any other person B. Again, the triangle may be more or less balanced in an affective sense. In that case X represents the community understood as the set of its members who are supposed to share the same forms, norms and values characteristic of the community. X corresponds in this case to the Generalized Other theorized by George Herbert Mead. If two people A and B have similar feelings, notions and interests (positive or negative) with respect to community X, the affective triangle is balanced, and between A and B there is a positive affective relationship, for example, a sense of fraternity, friendship or affinity. Otherwise, that is, if the two people have opposite feelings with respect to one and the same community, their relationship tends to be one of hostility. This is especially true for communities to which only one of the two belongs.

Social valence

By social valence I mean the subjective value that an individual consciously or unconsciously ascribes to any entity (person, object, medium, idea, activity, etc.) as likely to win him or her approval or disapproval (i.e., acceptance or exclusion) from the community to which he or she belongs. Take for example a person A who has to decide whether or not to buy a certain item of clothing X. In this case we have to consider a trilateral AXB relationship, where B represents the community to which he belongs, which has a certain feeling or judgment toward X. If B approves the purchase of X, then it takes on a positive social value. Conversely, if B disapproves of the purchase of X, then it takes on a negative social valence. The social valence attached to X influences A’s choice about the purchase of X. If X’s attraction to A remains very strong in spite of B’s disapproval, in order to balance the relationship it may happen that A begins to dislike his home community and contemplate moving to a different community that is favorable to X.

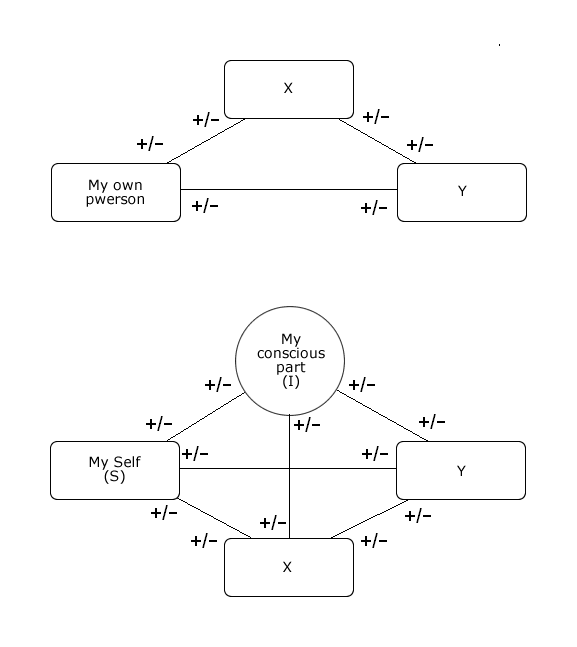

- my person

- X

- Y

where X and Y are any other entities (people, things, media, actions, ideas, etc.). We conceptually divide “my person” into “my conscious self” (I) and “my self” (S), meaning by “self” the whole individual excluding its conscious part. If we now draw all possible relationships between the four resulting entities, we obtain four triangles (SIX, SXY, IXY, ISX) as shown in the figure below.  We can now apply the equilibrium theory to the four triangles separately. From the subject’s (“my person”) point of view, the SXY triangle is unconscious, while the other three are conscious, that is, they can be examined by his conscious self, which can (if it has sufficient cognitive tools to do so) detect any affective imbalances and make decisions to resolve them. By the term metarelation I mean a relationship in which the conscious self is aware of itself (as separate from its self) and of all the relationships involved (the four triangles in the figure). This enables it to assess the affective coherence of each triangle and to decide on actions to resolve any imbalances. Of particular interest is the relationship between the conscious self (I) and its self (S). There can be a more or less positive or negative affective relationship between these two entities, which can result in cooperation or antagonism. For example, the conscious I may consider the habitual behavior of its self to be inappropriate and decide to begin psychotherapy to modify it. In turn, the self may resist control by the conscious self by resorting to distractions, excessive workloads, or consumption of alcohol or other drugs.

We can now apply the equilibrium theory to the four triangles separately. From the subject’s (“my person”) point of view, the SXY triangle is unconscious, while the other three are conscious, that is, they can be examined by his conscious self, which can (if it has sufficient cognitive tools to do so) detect any affective imbalances and make decisions to resolve them. By the term metarelation I mean a relationship in which the conscious self is aware of itself (as separate from its self) and of all the relationships involved (the four triangles in the figure). This enables it to assess the affective coherence of each triangle and to decide on actions to resolve any imbalances. Of particular interest is the relationship between the conscious self (I) and its self (S). There can be a more or less positive or negative affective relationship between these two entities, which can result in cooperation or antagonism. For example, the conscious I may consider the habitual behavior of its self to be inappropriate and decide to begin psychotherapy to modify it. In turn, the self may resist control by the conscious self by resorting to distractions, excessive workloads, or consumption of alcohol or other drugs.

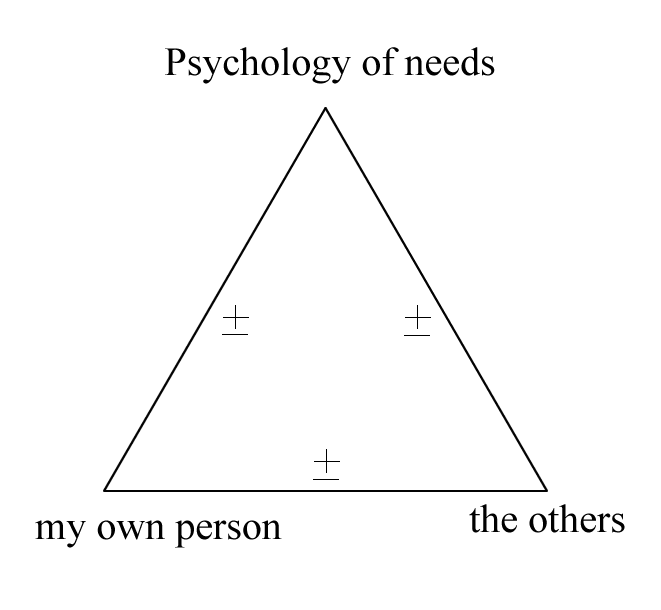

A triangle concerning me and this book

. The following figure represents the trilateral relationships between my person, others and this book.

- What opinion will others have of this book?

- How will others’ opinion of this book affect their opinion of my person?

- Will this book increase or decrease my popularity i.e., my acceptance by others, their esteem, sympathy, and affection for me?

- Did I do right or wrong in writing this book? What social reward will I get from it?

- Who will this book bother?

- Will this book help me improve my interactions with others?

- Will this book cause an increase or decrease in my sympathy for others?

- Will this book make me more sociable?

- What will others think of me by reading this book? Will they think I am an arrogant person? A conceited person? A deluded person? A failure? An ignoramus? Or a genius? A wise man? A highly educated one? Or is the fact that I wrote this book insignificant?

- Who will read this book? Who will appreciate it? Who will despise it? Who will criticize it? Who will find it useless? Who will ignore it?

I do not have an answer to these questions, but I find it very useful to have thought and verbalized them. If they remain unconscious, they might result in irrational answers that are far from reality, answers that would affect me unconsciously anyway. For example, they might diminish my motivation to complete, improve and make this book known.

Concluding remarks

The theory of affective balance and the concept of the trilaterality of relationships can be useful in understanding the social dynamics in which one is involved and making the most effective decisions to resolve any affective imbalances. These, in fact, in the long run can be a cause of stress and mental disorders. In fact, we can assume that cooperation needs include the need to resolve affective imbalances in trilateral relationships, that is, the need to maintain coherence between multiple affects.

Next chapter: Learning, imitation, empathy, conformity.